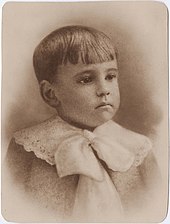

Known for his prolific works, many of which explored everyday Americans living through desperate conditions, Eugene O’Neill won 4 Pulitzer Prizes (a still unmatched record for a playwright) and he, himself, received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936. But the author’s life wasn’t always an unmitigated portrait of contentment––or success.

Born in a hotel room in 1888 to the actor James O’Neill, and his wife Ella Quinlan, Eugene began his life immersed in a world that would go on to become the backdrop of his profession: the theater. Touring the country with his father’s stage company, the young O’Neill became exposed to the seamy underbelly of show business, specifically alcohol, before he was a teen. A bright student, O’Neill was later accepted into Princeton before dropping out after his first year to move from Connecticut to New York––where he spent most of his time drinking and carousing with his brother.

By 1910, he had married his first of three wives, Kathleen Jenkins, although the union was short-lived due to O’Neill’s penchant for traveling. While out on a solo trip to Latin America, wherein he caught malaria, O’Neill returned home to find Kathleen pregnant. Upon giving birth to a son, Eugene O’Neill, Jr., he––without seeing the boy––shipped off again. Kathleen filed for divorce soon after. It was after this return that O’Neill decided to be a playwright.

Over the next five years, O’Neill would write a series of mostly one-act plays, honing his craft as an observational writer by incorporating much of his own traveling experiences into titles like, Into the Zone(1917) and The Long Voyage Home (1917). In 1918, he married Agnes Boulton and the two would have children, Shane and Oona. Professionally, it wasn’t until 1920 that critics and audiences began to take note of O’Neill’s writing, with the publishing of Beyond the Horizon (1918)––which would win the first of four Pulitzer Prizes.

Following this, O’Neill experienced a period of prolific writing, many of these plays dealing with fractured families and general misfortunes. Such characters were fragile and nuanced––but ultimately resilient, including those featured in Anna Christie (1920), The Emperor Jones (1920), The Hairy Ape (1922), Desire Under the Elms (1924), and Strange Interlude (1928)––the former and latter of which won him his second and third Pulitzer.

Despite professional success, O’Neill’s world was crashing down, what with the death of his mother, father, and brother, plus the dissolution of his marriage upon taking up with actress Carlotta Monterey (who we would marry less than one month after divorcing Boulton) in 1929.

The next decade saw the publishing of some of Eugene O’Neill’s best work, including Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), Ah, Wilderness! (1933) and The Iceman Cometh (1939)––featuring further examples of contemplative characters struggling with tragedy. By this time, he had also all but abandoned his children.

In 1943, Eugene O’Neill became father-in-law to famed comedian and actor, Charlie Chaplin who married 18-year-old Oona (Chaplin was 54). Despite the mild controversy, their marriage produced 8 children (including actress Geraldine Chaplin) and lasted until Chaplin’s death in 1977.

Sadly, O’Neill’s final years were spent mostly estranged from his family, as well as from much of the literary community. His failing health, and by now reclusive nature, was a boon for creativity, however, he followed up by making a series of wild and erratic decisions––like, destroying many of his manuscripts (fearing that they would be altered after his death) and asserting that certain plays, like the autobiographical Long Day’s Journey Into Night, not be produced for the stage during his lifetime. Also, a severe Parkinsons-like tremor had developed in his hand, which all but prevented him from writing new material.

Eugene O’Neill died in his room at the Sheraton Hotel in Boston on November 27, 1953. Though varying causes of death have been released over the years, it wasn’t until 2000 that it was discovered he died from a rare form of brain deterioration.

His final words, allegedly, were: “I knew it. I knew it. Born in a hotel room and died in a hotel room”.

Beyond the Horizon, 1918

A classic exploration of the bonds of loyalty, O’Neill’s Beyond the Horizon tells the story of brothers Andrew and Robert––the former, a steely and determined farmer destined to inherit the family stead; and the latter, a writer recently recovered from illness and set to sail the world with an uncle. Before Robert’s leave, he falls in love with Ruth, a girl-next-door type whom both families thought would marry Andrew. Given this newfound romance, Robert stays behind to be with Ruth and tend to the land while Andrew sets sail. However, years pass, and Andrew returns to find the farm desolate, their father dead, and Ruth a bitter shell of her former pristine self.

Anna Christie, 1920

Eugene O’Neill won his second Pulitzer Prize in two years, Anna Christie blends humor with melodrama in this explorative four-act play about the testing of familial bonds. Chris Christopherson is an old sailor who has spent his life at sea––much to the chagrin of his family, including his daughter, Anna, whom he hasn’t seen in years. Following the death of his wife, Chris sends Anna to live with relatives on a farm. After experiencing a lifetime of abuse at the hands of the men on the farm, Anna, now working as a prostitute, writes to her father in the hopes that she can come to New York and live with him until she gets herself back on her feet. Anna escapes the life she hates, only to find new challenges while grappling with her history of abandonment until a handsome sailor––just like her father––enters the picture.

Mourning Becomes Electra, 1931

One of Eugene O’Neill’s acclaimed masterpieces, Mourning Becomes Electra is a trilogy of tragic plays inspired by Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy––with a New England backdrop and an American Civil War timeline. The play follows the volatile Mannon family––Lavinia, who constantly fights with her mother, Christine, while waiting for the battlefield return of her father, General Ezra. All the while, as America attempts to return to a version of its former self, arrogance, hatred, and duplicity, along with dark secrets, threaten to fracture the Mannons to the point of murder. A study in psychological conflict, Mourning offers insight into family tragedy and its effect on the survivors.

The Iceman Cometh, 1939

Every night, the ramshackle saloon and rooming house owned by Harry Hope is teeming with a motley crew of New Yorkers from all walks of life, including two Boer War veterans, a once-wealthy gambler, and a former syndicalist anarchist. This ragtag team of drunken misfits has little in common other than the need for a stiff drink. It isn’t until a not-so-unexpected visit from their favorite, charming and newly sober traveling salesman, Theodore Hickman, that the members of this wily gang are forced to confront their habits and life choices and take a look at their sobering realities once and for all––while bearing the brunt of the consequences of such introspection.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night, 1941

Easily one of O’Neill’s most closely associated acts, not to mention one of the most lauded and studied plays in the history of American theater, Long Day’s Journey Into Night is a work so deeply personal (some say autobiographical) that the author himself insisted that it not be produced until twenty-five years after his death. Taking place over the course of a single day in the life of the tortured Tyrone family–– beginning in the morning, as the family gathers for breakfast, and concluding in the late evening––this four-act character study (James and Mary, along with their sons, Edmund and Jamie) is a daunting, yet seminal read for any fan of O’Neill.

Mary, subsumed by an addiction to morphine, watches helplessly as her family is overtaken by trauma––Edmund falls ill with consumption, while Jamie descends into a bitter, alcohol-fueled downfall––all the while James, a former successful actor, bemoans and dreams of the life he could have had. All of the Tyrones are haunted by their missteps and are eventually consumed by them.

A Moon for the Misbegotten, 1943

A Moon for the Misbegotten is the sequel to the events in Eugene O’Neill’s A Long Day’s Journey Into Night and centers around the elder Tyrone brother, Jamie Tyrone. Since he was last seen, Jim, as he is now known, is older and much more despondent, working as the landlord of the estate and spending most of his time drinking and socializing with his tenants. He is especially friendly with two renters: the hard-worn Irish ex-pat Phil Hogan and his domineering daughter, Josie, who has been secretly in love with Jim all the while. When Phil discovers that the stead is to be sold off, he concocts a plan for Josie to seduce a drunken Jim in an effort to thwart the sale. However, Jim, as Josie discovers, is haunted by the ghosts of his past, racked with misgivings and self-loathing torment, virtually incapable of love. A Moon for the Misbegotten is the story of a doomed man’s guilt and the woman who tries desperately to love him.

Eugene O’Neills Greatest Plays

Eugene O’Neill plays, many of which explored everyday Americans living through desperate conditions, Eugene O’Neill won 4 Pulitzer Prizes (a still unmatched record for a playwright) and he, himself, received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1936.

Eugene O’Neill Monologues

There can be no half way work when working on O’Neill and that is why it is important immerse yourself in his work as a young actor. In that spirit we have put together a list of Eugene O’Neill monologues for you to explore and work on.